A city shaped by division

For a long time, the Berlin Wall did more than divide a territory. It reshaped an entire city, slowly, deeply. East Berlin and West Berlin grew facing one another, close yet unreachable, forced to define themselves in contrast. In the streets, in the alignment of buildings, in unexpected gaps, the separation is still readable. In some places, clearly. In others, almost by chance.

Living in the city during those years meant adjusting to a border that intruded into everyday life. A familiar street turning into a dead end. A longer route, without explanation. A window suddenly sealed. The city shifted without warning. People adapted as best they could.

This border was never just concrete. It settled into habits, movements, the way neighborhoods were perceived. In the eastern part, its presence could be felt even when it was not visible. Empty spaces, controlled perspectives, silences built into the urban fabric. Understanding the Berlin Wall today still means learning to read this division written into the city, a fracture that disappeared physically, but was never entirely erased.

The Berlin Wall, a border that shaped the city

The construction of the Berlin Wall, during the night of August 12 to 13, 1961, resulted from a political decision taken by the GDR authorities, with the backing of the Soviet bloc. The aim was explicit, to put an end to the massive flow of East German citizens toward West Berlin, which had become one of the main escape routes to the West. Within a few hours, a city that was still porous found itself abruptly cut apart.

At first, this East German border took the form of barbed wire and provisional barriers. Very quickly, it evolved into a far more complex system. Concrete walls, watchtowers, trenches, restricted zones and surveillance devices came together to form what was then known as the inner-German border in the city. This was not a single structure, but a layered arrangement designed to control, deter and prevent any attempt to cross.

For nearly thirty years, this border imposed a heavy political and human reality. Neighborhoods were split in two, streets vanished, families were separated overnight. In East Berlin as well as in West Berlin, the separation reshaped movement, everyday uses of space and the relationship to the city itself. Berlin became a constrained territory, organized around a line of rupture dictated by the tensions of the Cold War.

The fall of this barrier, on November 9, 1989, did not stem from a clearly assumed decision at the top of the state. At that time, the GDR was led by Egon Krenz, at the head of a power already weakened. A confused announcement made by Günter Schabowski, during a press conference broadcast live, triggered the unexpected opening of the crossing points. Public pressure did the rest. Within hours, the division gave way.

Although the structure gradually disappeared from the landscape in the years that followed, its consequences continued to shape the city. The Berlin Wall remains readable in the urban space, no longer as a physical obstacle, but as the lasting legacy of ideological choices and poorly controlled decisions that left a deep mark on Berlin.

Where to see the Berlin Wall today

Today, this former border is not revealed only through a handful of imposing remains. More often, its traces dissolve into the city itself. A line on the ground, an empty strip of land, a break in the alignment of buildings. Signs that are sometimes subtle, sometimes obvious, but always telling of how the separation once cut through Berlin. A few places still make it possible to grasp, very concretely, how this barrier organized space and weighed on everyday life.

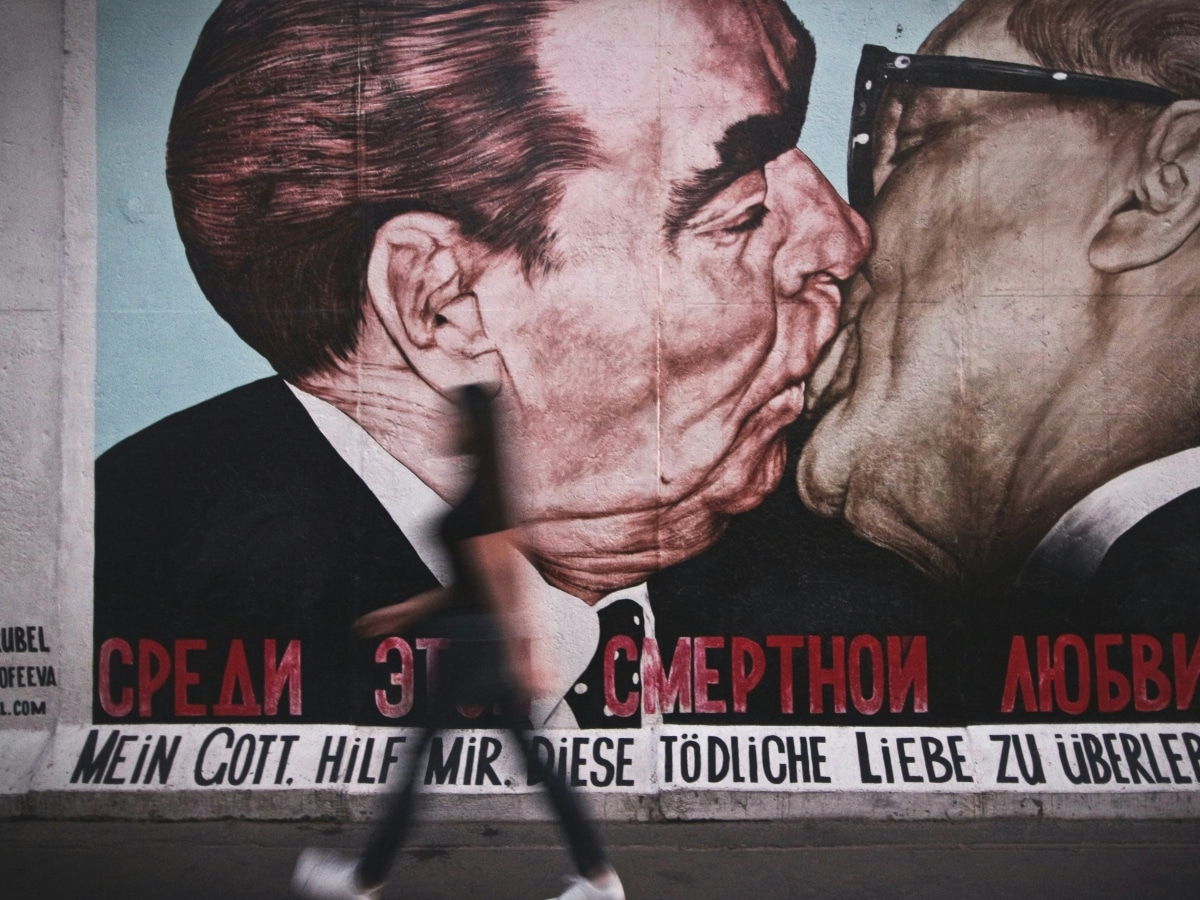

East Side Gallery

Along the Spree River, the East Side Gallery preserves one of the longest remaining visible sections of the former structure. After 1989, this stretch was taken over by artists who painted directly onto the concrete. The murals catch the eye, but what leaves the strongest impression is the sheer length of the wall. Walking alongside it, step after step, the physical reality of the division slowly becomes clear.

Bernauer Straße

Bernauer Straße offers an almost raw reading of the inner-German border. Here, the barrier ran directly along residential buildings. Facades on one side, sidewalks on the other. Some residents found themselves cut off from their own street. Today, the preserved structures, open spaces and visible route make it possible to measure the true scale of the border system and how deeply it intruded into daily life.

Checkpoint Charlie

Once a crossing point between East Berlin and West Berlin, Checkpoint Charlie carries a heavy symbolic weight. The site is busy, sometimes overwhelmingly so, yet it remains useful for understanding how controls were organized, how permits were checked, how waiting became part of the experience. Each crossing was a test. A quiet negotiation with the frontier, under constant watch.

The route of the Berlin Wall

Across the city, the former route of this separation is often marked by a double line of cobblestones or discreet plaques embedded in the ground. These markers follow the old line of division and now cut through lively neighborhoods, often without drawing attention. They serve as a reminder that the barrier was not limited to a vertical structure, but occupied a wider, carefully organized space, designed to be monitored at all times.

The Berlin Wall Memorial

Along Bernauer Straße, the Berlin Wall Memorial offers a more complete reading of the border system. Watchtowers, restricted areas, preserved segments. Together, they show that the frontier was a complex, structured device, built to last. Not just a symbol, but a heavy mechanism, embedded in the landscape and in people’s lives.

Berlin East today, between memory and renewal

East Berlin has changed, unmistakably so. But not all at once, and not at the same pace everywhere. Some places tell a story of visible renewal, almost immediate. Others retain a heavier atmosphere, shaped by the legacy of the GDR, sometimes without even trying to display it. Exploring these areas helps make sense of how past and present still coexist in today’s Berlin, sometimes smoothly, sometimes with a quiet tension.

Prenzlauer Berg

Once a working-class district in the eastern part of the city, Prenzlauer Berg has become a symbol of transformation. Renovated buildings, cafés spilling onto the sidewalks, parks filled with life. And yet, looking closer, something remains. In the layout of the streets, in certain volumes, in architectural details that do not pretend. The neighborhood has changed its face, but a memory still runs beneath the surface.

Friedrichshain

Friedrichshain captures well this meeting point between East German heritage and alternative culture. Wide avenues appear, residential blocks typical of the GDR, then suddenly a rougher energy. Posters, cultural spaces, terraces, movement. Here, the eastern districts are in constant dialogue with the present. Not always gently, but that friction is what keeps the area alive.

Alexanderplatz

Alexanderplatz remains one of the most emblematic reference points of the former eastern sector. Monumental urban planning, designed to express a certain idea of power and socialist modernity, still shapes the space. Today, the square concentrates shops, transport lines, continuous flows. People pass through, meet here, cross it. And beneath the agitation, a logic of another era can still be felt.

Karl-Marx-Allee

Karl-Marx-Allee offers one of the most striking examples of monumental architecture from the GDR period. Wide, almost theatrical, uniform in its façades. It was conceived as an ideological showcase, and it shows. Walking along this avenue makes it easy to grasp how urban space could become a political tool. Without speeches. Just through staging.

Volkspark Friedrichshain

As Berlin’s oldest public park, Volkspark Friedrichshain brings a sense of breathing space to the heart of the former eastern districts. A place used by residents, simply, without display. Here, another side of the city comes into view, more everyday, calmer. And perhaps this is where it speaks most clearly, this way Berlin has of reclaiming places long marked by history, without turning them into a spectacle.

Understanding Berlin beyond landmarks

Understanding Berlin is not just about visiting its most famous sites. The city reveals itself in other ways, through layers, ruptures and traces left behind by recent history. This former border and the story of East Berlin offer a useful perspective for grasping these contrasts and understanding why the city has kept such a fragmented identity.

To go beyond what is immediately visible, exploring these places with a local guide in Berlin often helps uncover nuances, unspoken stories and details woven into the urban fabric. Some things do not stand out on their own. They emerge slowly, while walking.

Frequently asked questions about the Berlin Wall and Berlin East

– Where can you still see traces of this former border today?

There are several places where remains are still visible, sometimes very directly, sometimes in more subtle ways. The East Side Gallery preserves the longest section still standing. Other locations, such as Bernauer Straße or the Berlin Wall Memorial, help explain the border system as a whole. Elsewhere in the city, the former route is simply marked on the ground, but it remains readable for those who take the time to look.

– Are East Berlin and West Berlin still different today?

Officially, the city has been reunified for a long time. In practice, certain differences remain. They can be felt in urban layouts, in the width of avenues, in some architectural ensembles, and in the atmosphere of specific neighborhoods. These contrasts are no longer political, but inherited from very different trajectories.

– How long does it take to understand the history of this division?

The main historical lines can be grasped in just a few hours by visiting key sites. But truly understanding what this border represented for the city and its inhabitants takes more time. Walking, observing, returning to certain places. And sometimes listening to those who know the local history in depth.

– Is this former barrier still visible in the urban space outside museums?

Yes. Many traces are integrated directly into the city itself. A double line of cobblestones, an unusual empty space, a break in the alignment of buildings. These signs often go unnoticed, yet they tell a very concrete story of how the separation once crossed Berlin.

– Why does Berlin remain marked by its divided past?

Because this boundary did more than separate a territory. It shaped how the city was built, how it was lived in, and how people moved through it for nearly thirty years. Those choices left lasting marks. Berlin rebuilt itself, but it never tried to completely erase that period. Instead, it absorbed it, sometimes quietly, sometimes more openly.