Immerse yourself in Prague's fascinating Jewish history

In Prague, most eyes drift toward Charles Bridge, the Castle, the Old Town Square. That’s where the crowds go. But another part of the city pulls at those who veer slightly off course. Josefov. The old Jewish quarter. Compact—just a tangle of streets—but dense in a way that feels almost physical. Centuries layered, moved, erased in places, but still there somehow.

You step into it without warning. No threshold, no shift in noise. Then the walls begin to say something else. Names etched in stone. Symbols that don’t explain themselves. A memory that doesn’t announce its presence but holds you anyway. The old Jewish Town Hall stands quietly, marked by a strange clock—Hebrew letters, hands turning counterclockwise. A tiny detail. But it stops you. One of those things that speaks without sound.

Josefov isn’t a postcard scene. It asks for time. For a slower pace. To follow the pull of the synagogues, each carrying its own tone, its own century. Take the Old-New Synagogue, for instance. It doesn’t try to charm. Sharp angles, dim light, nothing soft about it. And still—it’s stood here since the 1200s. There’s a tension in the air. Something harsh, almost cold. But alive.

History of Josefov: from the medieval ghetto to the present day

12th to 15th centuries: the formation of the ghetto

By the 12th century, a Jewish quarter had already taken shape in what would later be known as Josefov. Not by choice—walls went up, and those who followed the faith were pushed inside. A small, tight area. Narrow streets, stacked houses, little space to breathe. Life here wasn’t easy. Still, something grew. Scholars debated in dimly lit rooms. Traders did business. Craftsmen passed skills from hand to hand. Despite the weight of restriction, the community moved forward.

16th and 17th centuries: Josefov's golden age

The Renaissance brought a shift. And for Josefov, a brief moment of light. Mordechai Maisel, known for his wealth and quiet influence, played a key role. He helped fund buildings—synagogues, in particular. The Maisel Synagogue, the Upper Synagogue—they stood as both spiritual homes and symbols of stability. During these years, the ghetto became more than a boundary. It became a center for learning, for religious life, for the broader Jewish culture in Bohemia.

18th century: Joseph II's reforms

1781. The Edict of Toleration lands. Emperor Joseph II lifts some of the long-standing restrictions, not entirely—but enough to breathe differently. Josefov begins to open. The ghetto gets a new name—taken from the emperor himself. Symbolic, yes, but also a sign: a line between what was and what might come. The walls—literal and social—start to shift.

19th century: urban transformation

Everything changes again in the 1800s. Under the Austro-Hungarian Empire, progress becomes policy. Much of old Josefov is torn down. Streets widened. New façades built in Art Nouveau. The district blends into Prague—but in doing so, loses part of what made it distinct. History gets repaved. A new district rises, cleaner, grander, but a little emptier of memory.

20th century: the shadow of Shoah

Then the 20th century arrives, heavy with shadows. Under Nazi occupation, Prague’s Jewish population is nearly erased. Josefov is emptied. Stories vanish. Lives end. And yet, strangely, some places survive. Synagogues. The Jewish cemetery. Preserved, not out of respect, but because the regime had a darker plan—a museum to document a people they intended to erase. That plan failed. The buildings remain.

Today: a memorial district

Now, Josefov stands in stillness. Not untouched, but not forgotten either. Its synagogues, museum, cemetery—visited by thousands, year after year. Not just to look, but to learn. To pause. Some walk through quickly. Others stay longer, caught by the silence in the stones. Today, Josefov speaks not only of what was lost, but of what endured. History lives here—not polished, but present. A space between grief and resilience, in the middle of Prague.

Josefov's must-see synagogues

The Old New Synagogue: a witness to time

The Old-New Synagogue (Staronová synagoga) doesn’t shout its age—but it doesn’t need to. Built in the 13th century and still in use, it’s the oldest functioning synagogue in Europe. Solid. Quiet. Its Gothic walls carry centuries without ceremony. Inside, the space is stripped of decoration, almost austere. Which is part of its power. You walk in, and something settles.

A local legend tells of angels who carried the stones here, piece by piece. Maybe that’s folklore. But something sacred lingers. History and belief seem to meet here without needing explanation.

The Spanish synagogue: a Moorish jewel

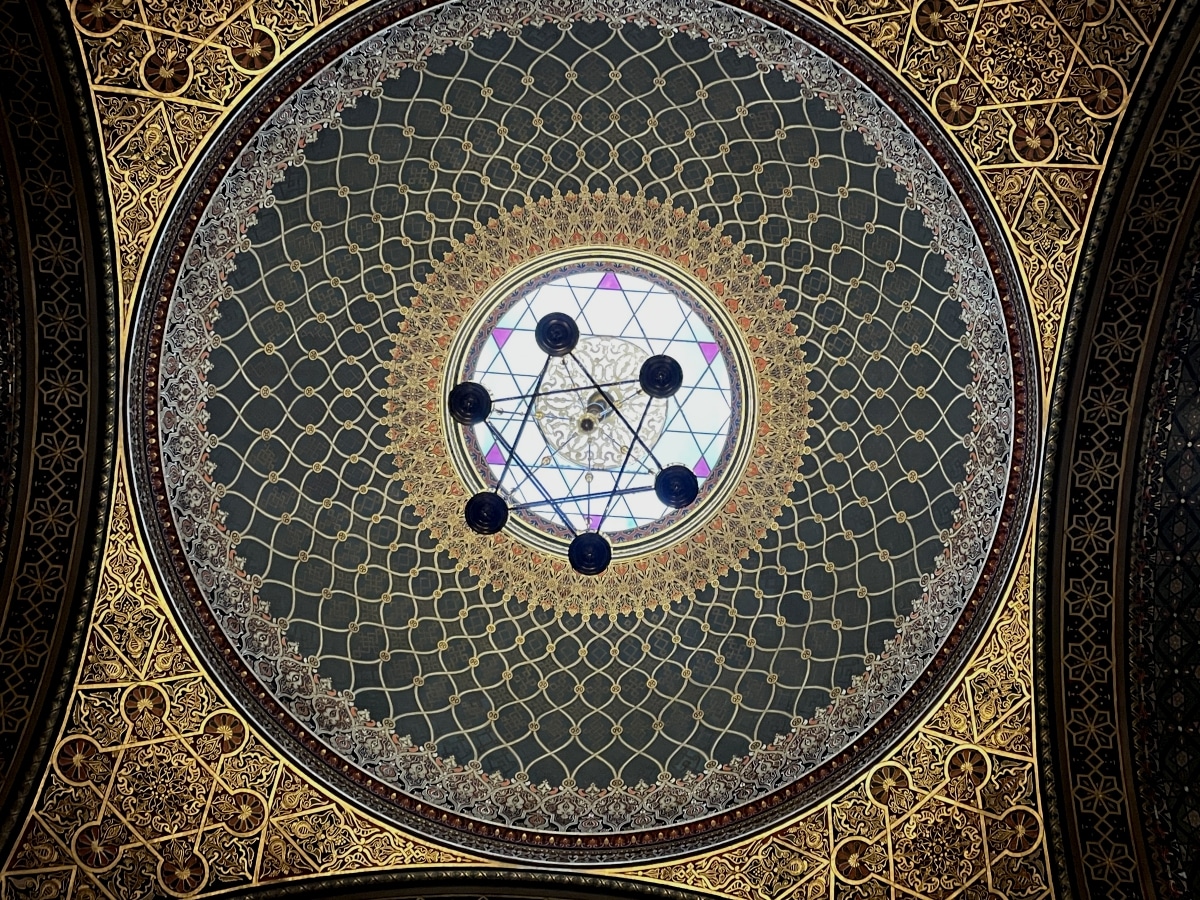

Down another street, something entirely different. The Spanish Synagogue (Spanělská synagoga), opened in 1868, shimmers with pattern and gold. Influenced by Moorish design, the space feels almost theatrical—every surface alive with detail. It’s named for the Sephardic Jews who once made this neighborhood their home.

Step inside, and the quiet becomes ornate. Domes, arabesques, light playing across gilded walls. It’s hard not to stop and just look. Not solemn like the Old-New. But no less powerful.

Pinkas synagogue: a moving memorial

Pinkas Synagogue (Pinkasova synagoga) speaks more softly, and its voice carries weight. This isn’t just a place of worship. It’s a memorial. On its walls—name after name. More than 80,000 Czech Jews lost during the Holocaust. The silence here is heavy, but not cold.

It doesn’t dramatize grief. It records it. Quietly. Relentlessly. And in doing so, leaves a mark deeper than words can reach.

Maisel synagogue: a place of Jewish history

Commissioned in 1592 by Mordechai Maisel, one of Josefov’s key figures, the Maisel Synagogue (Maiselova synagoga) once stood as a symbol of prosperity. Today, it’s part of the Jewish Museum, and serves as a record—artifacts, manuscripts, objects that trace the long arc of Jewish life in Bohemia.

The structure itself reflects Renaissance symmetry, though the exhibitions shift it into something more contemporary. If history interests you, this is where threads start to come together.

Klaus synagogue: a glimpse into religious life

Klaus Synagogue (Klausová synagoga) carries a quieter presence. Built in 1694 where three small buildings once stood—the “klausen” in old German—it now houses exhibits on Jewish ritual life. Ancient texts, ceremonial items, detailed displays of traditions that often go unseen.

It’s not grand. But it pulls you in. Shows how belief is carried in everyday objects. How identity survives through repetition, through practice.

The Upper Synagogue: a secret but fascinating place

Often passed by. The Upper Synagogue (Vysoká synagoga) doesn’t announce itself. It was once reserved for the Jewish council—less public, more internal. Built in the 16th century, it stands close to the old Jewish Town Hall, quietly holding its place in the district’s fabric.

Today, it belongs to the Jewish Museum and holds sacred items that once served a living community. It’s not grand. But step inside, and you get a sense—of decisions made, prayers whispered, a world once tightly woven behind these walls.

The old Jewish cemetery: a unique place in the world

Prague’s Old Jewish Cemetery, founded in the 15th century, doesn’t unfold like other cemeteries. It rises. Layer upon layer—graves stacked vertically, sometimes a dozen deep. Space was limited, but tradition forbade disturbance. So the solution was to build upward, over time, over memory.

Roughly 12,000 tombstones are visible now, though close to 100,000 people are believed to rest beneath them. The stones lean and overlap, carved names brushing against each other like echoes. There’s no tidy order here. Just a quiet, almost chaotic beauty. It feels like history trying to make room for itself. And somehow managing to do so.

A journey through time

Each stone in the Old Jewish Cemetery seems to hold more than just a name. Hebrew epitaphs, worn by centuries, still trace the outline of lives long gone. Symbols appear—lions, stars, crowns—each marking something: a family line, a profession, a trait that once defined a person. A teacher. A healer. Someone remembered for courage, or faith, or generosity.

The carvings aren’t decorative. They speak. Quietly. Walk through, and you begin to read—not just the letters, but the weight of a community that lived, struggled, and left traces behind.

Rabbi Löw's grave: a place of pilgrimage

One tomb draws more footsteps than the others. Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel, known as Rabbi Löw, rests here. A scholar from the 16th century. A mystic. The one associated with the Golem—a clay figure, said to have been brought to life to defend Prague’s Jews. His story crosses into legend, but the respect remains real.

Visitors pause in front of his grave. Some pray. Others write wishes, fold them into slips of paper—kvitlach—and tuck them between the stones. The tradition continues. The silence around his grave feels different. Focused. Still.

Preserving memory

The cemetery survived. Through centuries of change. Through the destruction of the Holocaust. Somehow, it remained. Now part of the Jewish Museum in Prague, the site stands as more than a relic—it’s a record. Not polished, not curated to perfection, but intact in the ways that matter.

For those walking through, it’s not just about looking. It’s about listening. To the creak of the earth, the tilt of a stone, the space between names. Respect matters here—so does time. A thoughtful visit means letting the place speak before moving on.

To step into the Old Jewish Cemetery is to step into centuries of memory. Stacked in layers, tangled but never erased. A sacred patch of land where grief, reverence, and survival still live side by side.

The Prague Jewish Museum: a treasure trove of knowledge

The Jewish Museum in Prague isn’t confined to a single building. It stretches across Josefov, weaving together stories, memory, and objects left behind. Since its founding in 1906, the museum has worked to preserve the cultural life of Jewish communities from Bohemia and Moravia. Not in a grand, distant way—but with attention, with care. Each site tells a different part of the story.

A unique collection in the world

What’s gathered here—it’s vast. One of the largest Jewish collections in Europe. Ancient prayer books, scrolls, ceremonial silver. Embroidered Torah curtains. Fragments of everyday life, like spice boxes or kitchen tools. Many of these objects were taken during the Nazi occupation, intended for a “museum of a vanished race.” What was meant to erase has become, instead, a way to remember.

Every piece carries something. Not just its design or age, but the life it once touched. A ritual. A home. A moment now gone but somehow preserved in fabric, wood, or ink.

A dive into history

Each building reveals something different. The Maisel Synagogue focuses on the centuries before destruction—when Josefov thrived, when Jewish life pulsed through these narrow streets. Inside, displays trace the evolution of communities across Bohemia and Moravia. Maps. Portraits. Fragments of legal documents and family heirlooms.

The Pinkas Synagogue speaks more quietly. Its walls, covered in names—tens of thousands—are difficult to take in all at once. The weight doesn’t settle right away. But it stays. The space doesn’t ask for emotion. It just allows it.

Focus on Terezín

One section holds something harder to carry. The children of Terezín. Their drawings. Their poems. Scribbled suns, trees, fragments of imagined freedom. These weren’t made to last. But they did. Saved from loss, they now speak with unsettling clarity. Small hands making sense of unspeakable things.

The exhibition doesn’t dramatize. It doesn’t need to. It simply puts their work in front of you. And lets the silence fill the rest.

Where to eat in Josefov?

After walking through Josefov’s synagogues, cemeteries, and museum spaces, the body needs rest—maybe a little warmth, something on a plate, a drink in hand. The district and its surroundings offer a mix of flavors, some steeped in tradition, others more experimental. Here are a few places to pause, breathe, and eat well.

Kosher Restaurants and Jewish Cuisine

- King Solomon Kosher Restaurant: Just steps from the main sites, this spot leans into Jewish culinary tradition. Gefilte fish, cholent, sweet pastries that taste like stories passed down. Strictly kosher, deeply rooted.

- Dinitz Kosher Restaurant: A more contemporary setting, but the flavors remain familiar. Traditional dishes, done cleanly, with care. A solid option for those keeping kosher—or simply curious.

Other addresses nearby

- Field Restaurant: A short walk away. Michelin-starred, yet still grounded. Plates arrive as small compositions—modern, seasonal, unmistakably European. Not kosher, but worth the detour if you’re after something thoughtful and refined.

- Lokál Dlouhááá: Loud, casual, full of locals. Svíčková, goulash, dumplings heavy with sauce. And beer. Cold, foamy, served without pretense. A good place to eat like the city does.

Cafes for a relaxing break

- Café Franz Kafka: A soft-lit corner named for the city’s most haunted writer. Sit with a pastry, a book, a long espresso. It doesn’t push. Just lets you stay.

- EMA Espresso Bar: For something more focused. Bright, clean, full of serious coffee people. Beans matter here. If you need a reset between sites, this is the place.

Practical tips for visiting Josefov

Josefov isn’t a place to rush. The weight of history, the quiet of the streets, the depth of what’s been preserved—it all asks for time. A full day is best. And with a little planning, the experience becomes much more fluid.

For a visit that goes beyond plaques and panels, consider connecting with a Prague tour guide. The right guide adds more than facts—stories, context, moments that might otherwise slip past unnoticed.

- Opening hours and days: Most sites—synagogues, the Jewish Museum, the cemetery—are open daily, except on Saturdays (Shabbat) and Jewish holidays. From April to October, expect hours from 9am to 6pm. In colder months, closing time shifts earlier, usually around 4:30pm. Always worth checking ahead, just in case.

- Package and combo tickets: A single ticket can open most doors. The Prague Jewish Museum combo pass includes access to the Old-New Synagogue, Pinkas, Maisel, Klaus, and Upper synagogues, plus the Old Jewish Cemetery and museum exhibits. Discounts apply for students, children, and families—best value if you plan to visit more than one site.

- Recommended itinerary: Begin at the Old-New Synagogue. From there, move through the museum exhibitions, then end at the Old Cemetery. The flow feels natural—history deepening as you go. It’s less about checking boxes, more about following the thread.

- Tips: Get there early. Especially during high season, crowds gather fast. Also, the streets here are cobbled and uneven. Good walking shoes help. No need to overthink it—just come prepared to wander.